Architectural clarifications

Consumer context

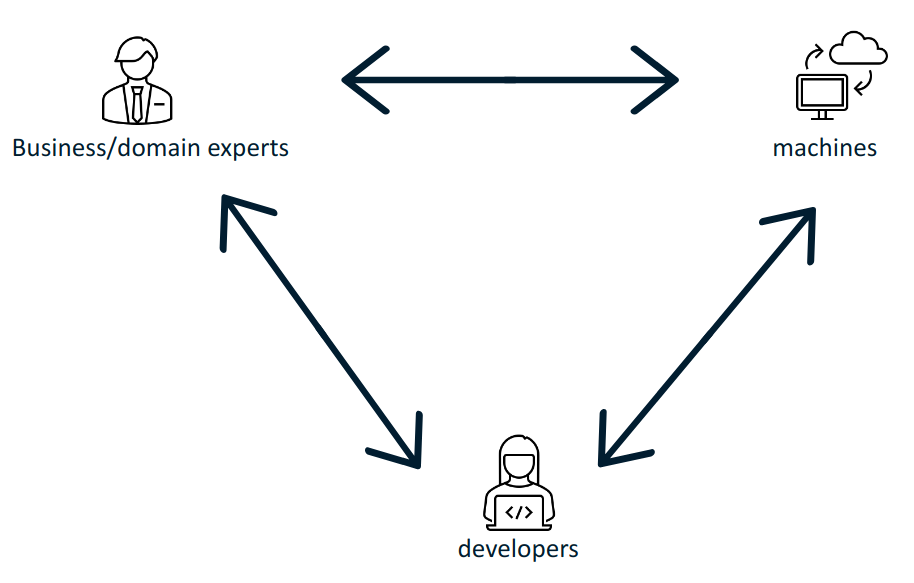

The consumers of SEMIC standards specification can be divided into three categories:

-

business users and domain experts,

-

technicians, software engineers, and software architects, the developers

-

software systems implementing the standards, the machines

The SEMIC goal is to bring these groups together, help them "speak the same language" and share meaning and conceptual references. Besides the very useful and much needed alignment of domains experts on what concepts mean, it is necessary to bridge the gap between domain experts and the technical experts who implement information systems. Then, the domain experts and business users shall interact with the information systems using the very same set of concepts, agnostic to and undistorted by the technology in the implementation process.

Standard semantic data specifications fulfil the purpose keeping these three groups in sync.

Ultimately, if the systems are based on standards the purpose is to build interoperable machines - machines that share data with each other and are able to operate on them seamlessly. The developers implement those machine interactions, and therefore the machines and developers must "find a common language". However, in order to ensure that the developers take the appropriate steps, the business/domain experts have to interact with them and convey their domain knowledge. This closes the loop: that the machine interactions correspond with the business/domain expert expectations.

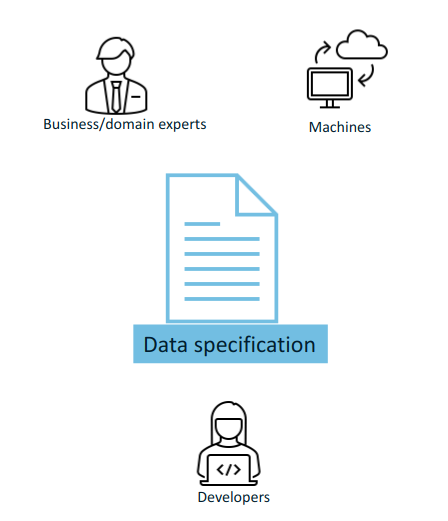

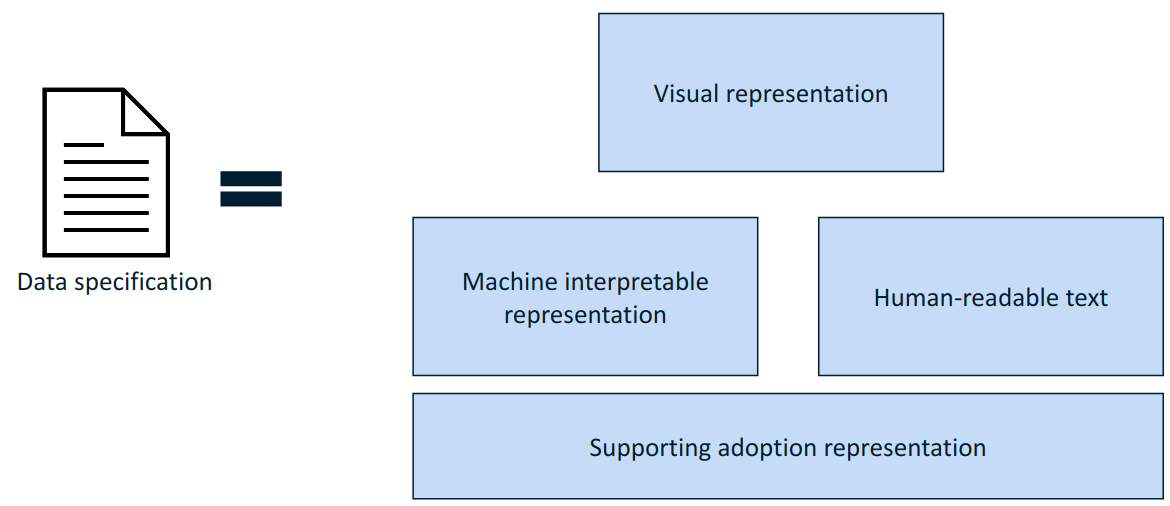

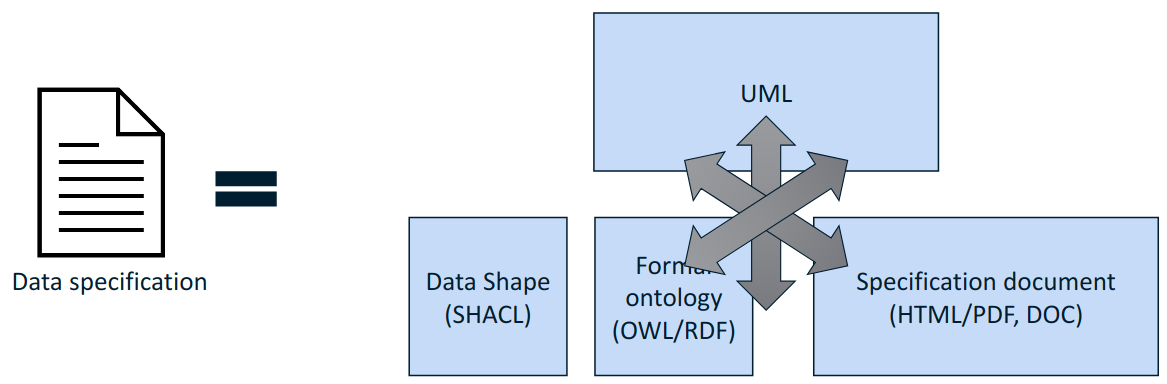

The data specification shall address the following information needs: visual representation, textual description, machine interpretable representation, and optionally additional representations that facilitate and promote adoption.

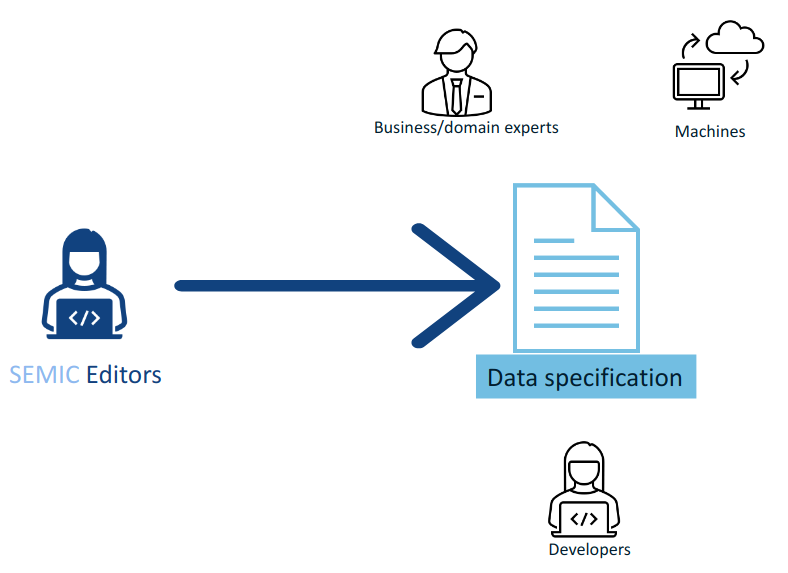

Editorial context

The aim of this style guide is to ensure the creation of coherent data specifications that can be read and used by domain experts, developers and machines. It is mainly meant for the editors of the data specifications (e.g. semantic engineers, data architects, knowledge modelling specialists).

Such data specifications are primarily developed in collaboration with domain experts. To achieve synergy with the domain experts, graphical representation is an indispensable medium that facilitates knowledge elicitation, ideation and knowledge organisation. This becomes especially relevant when shared conceptualisation needs to be attained within a Working Group.

Separation of concerns and transformation

The successful application of an ontology or the development of an ontology-based system depends not merely on building a good ontology but also on fitting this into an appropriate development process and implementation into an information system.

Generally, computing information models suffer from the intertwining of two types of semantic concerns. As George Box said, "All models are wrong, but some are useful", and what a model is useful for depends on what concern it is primarily addressing. On the one hand, the model represents (purely) the domain; on the other hand, it represents the implemented system, which encompasses a representation of the domain (domain knowledge intertwined with technical specificities). These different representation requirements place different demands upon its structure [partridge13]. For example, the concept of "location" can be described by domain experts (in a domain model) in a way that is not isomorphic to how the "location" class may be appropriately modelled for an information system (i.e., captured in an Implementation Model).

One of the common ways to manage this problem is by separating concerns. We take inspiration from OMG’s Model Driven Architecture (MDA) [mda], which is a well-documented structure where a model is built for each concern, which is transformed into a different model for a different concern. This approach is adapted to the SEMIC needs.

Transformation deals with producing different models, viewpoints, or artefacts from a model based on a transformation pattern. In general, transformation can produce one representation from another or cross levels of abstraction or architectural layers [mda-guide].

Separation of concerns in SEMIC

The Core Vocabularies (CVs) and the specialised Application Profiles (APs) aim to address the following concerns:

-

Domain experts need to agree on the definitions of concepts, relations and their organisation to form a coherent domain model expressed with varying levels of details and expressivity [SC-R2], a shared conceptualisation.

-

This is addressed with conceptual models expressed in UML.

-

-

The shared conceptualisation needs to be explicitly represented in a usable format (i.e. operated on) by the machines.

-

This is addressed with lightweight ontologies expressed in OWL 2.

-

-

In practice, to achieve interoperability, it is necessary to provide a (minimum and necessary) set of constraints supporting the ontology instantiation.

-

This is addressed with data shapes expressed in SHACL.

-

-

To facilitate reuse and understanding, a specification shall be accessible to the community as clear, complete and well-articulated documentation.

-

This is addressed with data specification documents expressed in HTML.

-

In addition, when multiple artefacts addressing each concern are produced, keeping them in synch is a serious editorial and maintenance burden that needs to be considered.

Editorial synchronisation problem

On the editorial side the artefacts composing a data specification need to be kept in sync. A modification done in one shall pervade and propagate in all others. This is a difficult, tedious and expensive activity if such synchronisation is to be done manually.

Experience shows that using a pivot representation as a single source of truth is a viable solution. Such representation needs to be expressive enough to fulfill all the information needs of the derived artefacts.

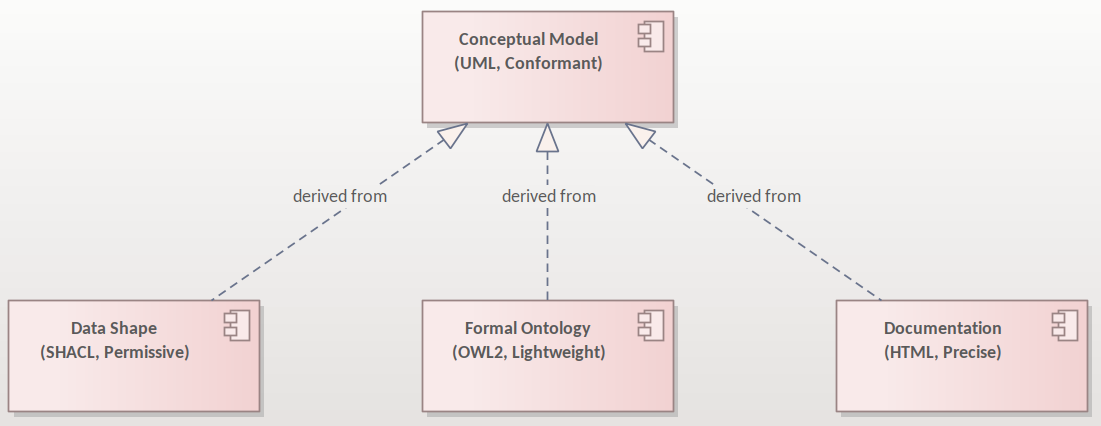

Transformation of the conceptual model

UML conceptual models can be used as the single source of truth [CMC-R1]. This means it is sufficiently expressive to capture multiple modelling aspects/concerns simultaneously. The other artefacts are then fully or partially derived from the conceptual model.

With UML as the single source of truth, the update process is easier to perform as it only has to be done in a single place. The other representations are automatically derived from the conceptual model; the maintenance is less error-prone, uniform and easy [Transformation].

This approach facilitates consistent maintenance of semantic data specification interrelationship and solves the editorial synchronisation problem.

However, using UML is not enough, by itself, as the risk of ambiguity and multiple interpretations of the meaning of the UML model elements used in the conceptual model still exists. This risk is mitigated by adopting precise interpretation rules, such as the ones provided in this style guide [CMC-R2]. The different concerns that each data specification is trying to address might lead to different interpretations of the same UML constructs. Therefore, [CMC-R2] defines only a minimal set of such interpretation rules (that can be further extended, if necessary).

Additionally, UML cannot cover all potential needs specific to each derived representation. Therefore, the scope of this architecture is limited by what can be expressed in UML and how that information is utilised to generate formal statements. But from our experience it is sufficient to cover all the needs of establishing semantic interoperability standards.

Relations between the artefacts are depicted in the figure above. The conceptual model is the source from which a) the data shapes, b) the formal ontology and c) the data specification document can be generated. Each artefact in the figure is qualified with two terms, the representation standard and the most characteristic feature. The conceptual model is expressed in UML language and shall be conformant with the conventions provided in this style guide and the interpretation rules [CMC-R2]. The formal ontology is expressed in OWL 2 language and shall be lightweight as indicated in this convention [SC-R2]. The data shape is expressed in SHACL language and is characterised by the appropriate level of permissiveness [DSC-R2]. The documentation is represented in HTML format and the wording used shall be as precise as possible to capture the meaning accurately and clearly express the intention of the authors.

Although not shown in this diagram, the generation of other artefacts is not excluded. For example, more heavyweight ontologies (i.e. with higher level of logical expressivity) can also be included in the data specification as additional artefacts (see note on [SC-R2]).

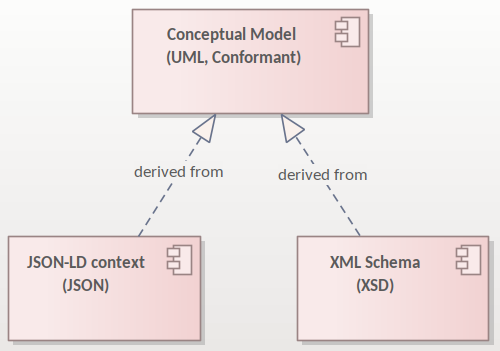

The figure above depicts that it is also possible to derive from the conceptual model additional artefacts, such as the XSD or JSON schemas and JSON-LD context definitions. These, however, are not addressed in this style guide.

One condition the conceptual model shall satisfy is that it shall comply with a set of pre-established conventions (general conventions and UML conventions) and have a fixed interpretation [CMC-R2].

The guidelines in this document enable and constrain the transformation process, making it precise enough to implement a toolchain that automatically performs conformance checking and necessary transformation operations. How this is done, however, is beyond the scope of this document, and the reader may refer to SEMIC toolchain [semic] or other similar implementations such as model2owl [model2owl] or OSLO toolchain [oslo-toolchain] projects.

Data specification and artefact types

For any given data specification, various concerns shall be addressed separately, each in a dedicated artefact type. Therefore, the CVs or APs shall be published as a set of artefacts, each addressing a specific concern. The union of these artefacts forms the intended semantic data specification [What is a semantic data specification?].

The table below summarises which artefacts shall be published for each type of data specification addressed in the SEMIC context.

Conceptual model (UML) |

Ontology (OWL 2) |

Data shape (SHACL) |

Specification document (HTML) |

Model diagram (PNG) |

|

Core Vocabulary |

Mandatory |

Mandatory |

Optional (shall be permissive) |

Mandatory |

Optional (recommended) |

Application Profile |

Mandatory |

Optional (shall be an extension) |

Mandatory |

Mandatory |

Optional (recommended) |

Artefact types

The semantic data specifications, both CVs and APs, are conceived as a union of specification artefacts, each addressing a different aspect/concern:

-

conceptual model expressed in UML

-

formal ontology expressed in OWL 2

-

data shapes expressed in SHACL

-

data specification document realised in HTML

-

conceptual model diagrams expressed in any image format (PNG, for example)

Data specification types

In the SEMIC context two types of data specifications are of main concern (a) Core Vocabularies designed with broad interoperability goals and (b) Application Profiles designed with application oriented interoperability goals.

In this document, we will refer to these data specification types to provide guideline refinements depicting variations based on the data specification type. The primary concern and the intention in each of them differ as follows:

-

Core Vocabularies aim at establishing the shared vocabulary as a lightweight ontology essentially, and optionally some data shapes if necessary [Core Vocabulary].

-

Application Profiles aim at setting carefully designed data shapes on reused concepts from one or several existent ontologies and, optionally, a minimal ontology with specialised vocabulary [Application Profile].

The secondary concerns are present and common in both data specification types and are, in fact, instrumental to consistent production, maintenance and publication:

-

Editing of the conceptual model

-

Production of data specification document

The data specification’s artefacts are not independent but tightly interrelated and transformed from one form into another one.

Technical artefacts and concerns

It is difficult to draw a clear line between semantic and technical interoperability artefacts and concerns. This section aims at providing some guidelines and hints on how to distinguish between the two (but no guidelines on technical artefacts are considered as this is out of scope of this work). The best way to look at them is in terms of concerns addressed within each layer, which resembles a lot the discussion on distinguishing "Conceptual Data Models", "Logical Data Models" and "Physical Data Models" in ANSI [ansi] from 1975.

EIF [eif] defines the technical interoperability as covering the applications and infrastructures linking systems and services. The concerns considered in this layer are related, but not limited, to:

-

interface specifications,

-

interconnection services,

-

data integration services,

-

data presentation and exchange,

-

secure communication protocols,

-

access boundaries,

-

information boundaries, etc.

The technical layer deals with how to represent, how to transmit data, how the data/entities are bundled when served by a service (i.e. API design or transmission, with impact on performance, usability, and interface), what are the access rights, how is the security ensured, access and storage performance, interfacing with the service, usability, etc.

EIF defines the semantic interoperability as ensuring that precise (format and) meaning of exchanged data and information is understood throughout exchanges between parties: "what is sent is what is understood". It covers two aspects: semantic and syntactic. The semantic aspect refers to the meaning of data elements and the relationship between them. The syntactic aspect refers to describing the exact format of the information to be exchanged in terms of grammar and format.

The concerns considered in this layer are related, but not limited, to developing vocabularies and define data meaning in exchanges. This layer is agnostic to access right, security, transmission protocol, physical representation, how it is presented to the user, etc.

In the SEMIC context, Semantic Web and Linked Data technology standards are chosen by default. This means that the syntactic aspect is covered by the RDF specifications [rdf], whereas the semantic aspect is addressed within the Core Vocabulary and Application Profile, expressed in OWL 2 [owl2] and SHACL [shacl] languages.

Connecting the semantic layer and the technical layers may not always be straightforward. Three types of technical artefacts are of a particular importance, which rely on three different technologies: XML and XSD, JSON and JSON schema, and relational databases. We briefly comment on each below.

RDF. In case the system is gnostic of Semantic Web technologies, if the implementation uses RDF natively, then the technical layer is (near) isomorphic to the semantic specification. There is a perfect alignment.

JSON. When system implementation is based on JSON representations, a mapping shall be provided to establish semantics-syntax alignment. Luckily, how such an alignment is done is already specified in the JSON-LD standard specification [json-ld]. It contains a canonical mapping algorithm. The syntaxt semantic binding is provided by the so-called context definitions.

As a consequence, if the JSON structure is ought to be aligned with the semantic specification, it imposes a strong constraint on how it shall be organised, otherwise the mapping is not possible. So, an advantage of JSON-LD is that the semantics gets coupled nicely with the syntax, and it is in the reach of the developer.

XML. When the system implementation is based on XML representation, then the interplay between syntax and semantics is more problematic, as there is NO canonical way os linking the two. The only transformation we have is the XSLT [xslt] but no mapping language exists like in the case of JSON-LD. Hence, if one provides a mapping to an XSD schema, then one must also provide the XSLT specification that interprets that mapping. Furthermore, when we want to establish an alignment between syntax and semantics there is no constraint on the structure (like in the case of JSON). It is only good practices and alternative technologies, such as RML, that we can rely on in this case. [rml].

RDB. If the implementation is based on relational databases, the story is similar to the XML. There is no organic way of mapping syntax and semantics. The mapping is at the level of the database schema, and there is no canonical way of doing this. So, just like in the case of XML we rely on good practices and alternative technologies to encode an interpretation, such as D2RML [d2rm] and RML [rml].

Ideally, syntax-binding artefacts that show how to map from a semantic data specification into technical layer artefacts is also provided as part of the specification. Showing how to interface with the semantic layer is especially important when Application Profiles (and Implementation Model specifications) are developed and published.